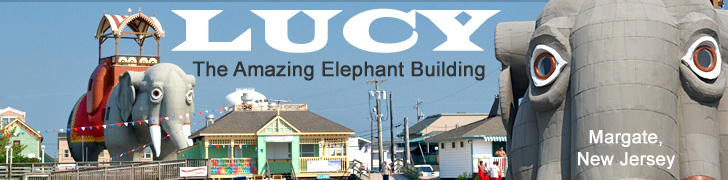

A national historic site as well as a unique example of the eccentric architecture of the late Victorian age, Lucy the Elephant is arguably the most beloved tourist attraction in the Atlantic City area. Located in the neighboring town of Margate, the 139-year-old elephant-shaped structure has come to the brink of demoliton several times, only to be saved by outpourings of public protest and grass-roots fund-raising fervor.

Lucy's massive size is apparent in comparison to the adjacent souvenir shop (above, left). She stands at the edge of the sand, looking out at the ocean beach that is one of the region's favorites. Visitors can climb into the ornate howdah atop the elephant's back for a bird's eye view of that beach below.

Windjammer logs from over the last century indicate that on clear days Lucy is visible from eight miles

Photo: Mary Godleski

|

| Among other things, Lucy Elephant is a place of love stories -- she is used for weddings and is otherwise the site of wedding proposals by lovers who feel some sense of connection to her. Here, a couple married inside the elephant building stands for a portrait near her hind legs. | out at sea, thus making New Jersey's the only coastline in the world marked by a six-story-high, elephant-shaped navigational aid. ( Go inside the beast.) The result of an 1881 exercise in stuntmanship and land speculation, Lucy was created as the attention-getting centerpiece of James V. Lafferty's beach real estate sales venture. Lafferty, a brash, 25-year-old entrepreneur, was driven by a vision for a new kind of real estate promotion that would lure prospects to the desolate stretch of sand dunes and scrub pine he hoped to sell as plots for vacation cottages.

Animal-Shaped Building

Atlantic City at that time was fast growing into a Victorian vacation metropolis centered around the Absecon Lighthouse, the landmark that was then the symbol of the seaside resort. Lafferty wanted to establish a similarly impressive landmark and sense of place for his own new development in "South Atlantic City." To gain the attention of the public and press, he chose what was then an unusal concept for U.S. audiences: a building shaped like a gigantic animal.

Architect and Patent Attorney

Retaining an architect, Lafferty, in 1881, set out to design a building in the shape of an elephant from the exotic land of the British Raj celebrated in the period's illustrated adventure magazines. Simultaneously retaining a patent attorney, Lafferty also sought to prevent anyone else in the United States from constructing animal-shaped buildings unless they paid him royalties. The U.S. Patent Office examiners, who appear to have been unaware of previous elephant building designs and constructions in Europe, judged Lafferty's idea to be an original, new and technologically significant concept. In 1882, they granted him a patent giving him the exclusive right to make, use or sell animal-shaped buildings for seventeen years.

A 90-Ton Sculpture of Wood and Tin

More sculpture than carpentry, the construction of Lucy involved hand-shaping nearly a million pieces of wood to create the required intricate collection of curves and appropriate load supports for a 90-ton structure finished in 1882 with an outer sheath of hammered tin. The amazing elephant building, which DID generate the publicity Lafferty hoped for, was the first of two he constructed (and a third whose construction in Cape May he merely licensed). The largest -- a gargantuan, twelve-story structure twice as large as Lucy -- called the "Elephantine Colossus" was erected in the center of the Coney Island, New York, amusement park. The third elephant associated with Lafferty, was the slightly smaller than Lucy "the Light of Asia," erected as the centerpiece of another real estate developer's program in South Cape May. The Collossus later burned down and the Light of Asia was torn down, leaving Lucy the only survivor.

A Life Beyond Real Estate

By the late 1880s, although the elephant buildings were drawing crowds of awed spectators, Lafferty's over-extended real estate

|

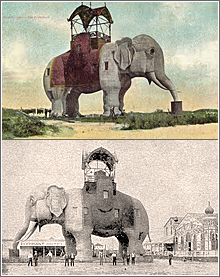

| When she was first built, as this early postcard shows (above, top), Lucy stood alone on an empty stretch of beach along which James Lafferty hoped to sell lots. As the area built up, this second postcard shows (above, bottom) how Lucy in her heyday became the "Elephant Hotel" and a major attraction for the summer horse-and-buggy crowds pouring into nearby Atlantic City. | ventures were losing money. Lucy and his surrounding Absecon Island holdings were sold to the Gertzen family, that operated the elephant building alternately as a tourist attraction, miniature hotel, private beach cottage and tavern. Meanwhile, "South Atlantic City" developed into a thriving shore community that later changed its name to Margate. In 1920, Lucy the Elephant tavern was forced to close by the passage of Prohibition. When that law was repealed in 1933, she immediately became a bar again. In the 1950s, as a new America emerged from World War II to build webs of superhighways and adopt airplanes as a cheap new way of travel to exotic vacation destinations, Lucy faded from the public's attention and fell into disrepair. By the 1960s, she was a dilapidated public safety hazard slated to be torn down.

Saving Lucy

In 1969, just ahead of the wrecker's ball, the "Save Lucy Committee" formed by the Margate Civic Association began two decades of public struggles that moved Lucy to beachfront land owned by the city and restored the peculiar structure as a historic site and tourist attraction. Since 1973 enough money has been collected in determined "Save Lucy" campaigns to restore the structural integrity and exterior of the 90-ton wood-and-tin pachyderm. But the fundraising battle continues today as the group works to raise additional money required to underwrite the never-ending costs of maintenance and fighting rust, rot and even lightening strikes on the great wooden beast.

All Rights Reserved, © 1998-2012 Hoag Levins

Contact: Hoag@Levins.com

About the author

|