Aside from being the first nearly complete dinosaur skeleton ever found and the first to be mounted, Haddonfield's Hadrosaurus foulkii was also the event

|

| American Museum of Natural History |

Haddonfield resident Edward Drinker Cope at age 30 in 1870, two years after the start of the Bone Wars when he was planning his first trip to hunt fossils in the West.

|

that gave rise to what became known as "The Bone Wars."

That's the popular name for the decades-long feud between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, each of whom was determined to be recognized as the country's leading authority in the new field of dinosaur paleontology.

Few competitions in the era of modern science have been as lengthy, as dramatic or as pointedly nasty. Both men rushed to find, excavate, document, officially name and claim scientific credit for the discovery of new kinds of prehistoric creatures whose existence had been definitively proven by Hadrosaurus foulkii.

Fueled by ego and separate family fortunes, Cope and Marsh raised small armies of bone hunters to range across the continent, often shipping back fossils by the ton.

Anchored in Haddonfield

The nineteenth-century Cope-Marsh saga is well documented and, over the last century, has been the subject of a shelf worth of books. But what is less well known is that much of the action of the Bone Wars was anchored in Haddonfield, N.J.

In 1858, when the skeleton of Hadrosaurus foulkii was extracted from a Haddonfield marl pit, a small circle of fossil cognoscenti realized that similar prehistoric skeletons were likely to be present

|

| Photo: Hoag Levins |

The "Bone Wars" between Edward Cope and O.C. Marsh has been the subject of a shelf full of books over the last century.

|

elsewhere in the marl deposits that underlay much of southwestern New Jersey.

Marl was a mineral-rich, clay-like substance that was the nineteenth century's leading farm fertilizer. The residue of an ancient Cretaceous sea bottom, it was dug from pits and transported to nearby fields to be plowed into the soil. Diggers had often hit and heaved aside fossilized bones, teeth, seashells and petrified wood as they worked. But immediately after the Hadrosaurus foulkii discovery, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia sent a flier to area marl pit operators asking them to alert the Academy when any fossil bones were struck.

Young bone hound

And the most intense investigator of those subsequent marl pit bone finds was young Edward Cope. Son of a wealthy Philadelphia Quaker family, Cope was a child prodigy who made himself an expert in the anatomy of lizards and snakes by his late teens.

In 1858 -- the same year Hadrosaurus foulkii was disovered and its bones transported to the Philadelphia Academy by Dr. Joseph Leidy -- 18-year-old Cope went to work for Leidy at the Academy. There, amidst the excitement of Leidy's pioneering documentation of dinosaur anatomy, Cope began recataloging the facility's large collection of reptile skeletons. Within a year, he had published the first of what would be a stream of scientific papers. In 1861, at age 21, he was elected a full member of the Academy.

By 1865, Cope had been appointed secretary of the Academy at the same time he was teaching as a professor of natural history at Haverford College, just outside Philadelphia. His spare time was spent across the Delaware River,

|

| Photo, claw: ANS, Phila. |

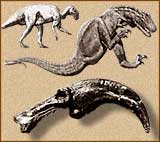

In 1866 Cope discovered the world's second nearly-complete dinosaur skeleton in a marl pit south of Haddonfield. The creature, Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (foreground), was a meat-eater that hunted members of the Hadrosaurus foulkii (rear) family. At bottom of image is one of the slashing claws of Cope's Dryptosaurus.

|

bone hunting through marl fields to the north and south of Haddonfield.

In the summer of 1866, in a pit of the West Jersey Marl Company in Barnsboro, twelve miles south of Haddonfield, Cope excavated the world's second nearly-complete dinosaur skeleton. He initially called the creature Laelaps aquilunguis -- a scientific name that was later changed to Dryptosaurus aquilunguis.

Move to Haddonfield

Within a year of that dramatic find, Cope quit his job at Haverford and was preparing to move his wife and infant daughter to a home on Kings Highway in the center of Haddonfield, where he would be closer to the marl pits. Now a curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences, his own dinosaur discovery as well as his scientific publications were beginning to suggest him as a possible rival for the fame that had been focused exclusively on his mentor, Dr. Leidy, then North America's preeminent paleontologist.

In 1868, now a Haddonfield resident, Cope worked with Leidy and their curious new colleague, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, on a novel project to mount the bones of Hadrosaurus foulkii in a life-like pose in the Academy's museum. Hawkins was a British artist who specialized in creating dramatic exhibits of real and hypothetical animals.

As news of the museum project spread, it drew the keen interest of natural scientists and their museums throughout North America and Europe. One of those expressing collegial curiosity in learning more about the Hadrosaurus foulkii mount as well as the New Jersey marl fields documented in Cope's writing was Othniel Marsh, a professor at the institution then known as Yale College in New Haven, Conn.

In 1867, after being appointed America's first college professor of paleontology, Marsh began collecting dinosaur tracks in the Connecticut Valley and was now expanding his explorations and quest for new bone finds.

Start of the Bone Wars

In 1868 he came to Haddonfield for a two-week visit and

|

|

Peabody Museum of Natural History |

|

|

34-year-old Othniel Charles Marsh in 1865, three years before he came to Haddonfield to tour the surrounding marl pits with Edward Cope.

|

|

tour of the southern New Jersey marl fields with Cope. The men jointly hunted fossils on that excursion, finding partial structures of two different prehistoric animals. Cope introduced Marsh to all the marl pit managers and foremen who regularly sent word to Haddonfield when their workmen struck bone.

Shortly after Marsh left, Cope learned that the Yale professor had quietly gone back for private visits with the various marl pit managers and offered them money to send their alerts and bones to New Haven rather than Haddonfield.

That 1868 bit of rivalry was the beginning of the Bone Wars. From then on, Cope and Marsh would maneuver against each other, spying, luring away each other's workers, bidding up the price of bones, publicly attacking the validity of each other's scientific findings, and otherwise working to undermine the other's professional reputation and accomplishments.

At the same time in the 1870s, the general understanding of America's dinosaur fossil reality was changing. There was new emphasis on the potential of largely unexplored western lands that were once the swamp and shoreline of a vast inland Cretaceous sea.

Marsh headed west in his first expedition in the summer of 1870; he led a team of Yale students prospecting for bones in desolate high-prairie areas where western Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado converge. Meanwhile, from his Haddonfield home, Cope planned his own first expedition to this same area for the following summer. Both men made major discoveries during those initial forays.

Frontier bone diggers

In a competition that quickly took on the air of a frontier military engagement Cope and Marsh used U.S. cavalry forts as staging areas and mule-drawn covered wagons as vehicles. They and their gangs of diggers spent the next twenty years unearthing amazing new prehistoric skeletal remains.

During his first trip West in the summer of 1871, Cope wrote home to his five-year-old daughter, Julia: "I have been traveling about in this country looking for fossil bones of huge animals such as I bring home in my bag to Haddonfield sometimes."

From the moonscape-like badlands of western Kansas, he wrote back to his wife, Annie: "The weather is lovely. The Indians are peaceable... Prairie dogs and antelope are in thousands and the wolves howled at us as we worked on the bluff."

That winter, back in his home on Kings Highway, Cope wrote his official report on that first trip through the desolate wilderness of western Kansas, describing how ancient seashells littered the ground and how the jaw bones of gigantic prehistoric monsters protruded from limestone cliff sides.

Far more than bones

Cope was a gifted narrative writer and one of the first scientists who attempted to evoke a total sense of primordial environment in his interpretations of his fossils. For instance, both Marsh and he had discovered pterodactyls of enormous size during their first western trips. One of Cope's was an awesome giant with a 25-foot wingspan. Sitting in his Victorian study, Cope wrote of it in a manner that gave both a report on the anatomical features of a new find as well as a vivid sense of what life would have been like for such an animal:

"These strange creatures flapped their leathery wings over the waves, and often plunging, seized many an unsuspecting fish; or, soaring, at a safe distance, viewed the sports and combats of more powerful saurians of the sea. At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore, and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs."

Throughout the 1870s, Cope managed his side of the continent-spanning Bone Wars from his Haddonfield home, which even had a barn outfitted as a paleontology workshop and manned by a full-time bone preparer. Each summer, Cope headed West to oversee his bone digging crews; each winter he spent writing the papers and books that documented his finds and made him an international star in scientific circles. In between all of this, he occasionally traveled to Philadelphia to attend his continuing duties as an official at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

At the end of the 1870s, when he moved his family back to Philadelphia to be closer to the greatly expanded Academy in its new location, he required two adjoining townhouses to hold the huge trove of fossils and papers he had amassed in his Haddonfield mansion.

Period of greatest achievement

His principal biographer, Henry Fairfield Osborne, wrote that "The decade of 1870 to 1879... was the golden period in Cope's life; the period of his greatest achievement, of his incomparable western expeditions, of the acquirement of the greatest part of his fossil collections, of the foundation of his principal scientific discoveries."

Part of that achievement was the discovery of 56 different species of dinosaurs. His arch rival, Marsh, is credited with discovering 86 dinosaur species.

|