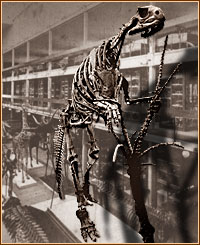

In 1868, ten years after it was discovered in Haddonfield, N.J., the skeleton of Hadrosaurus foulkii was put on public

|

|

Photo: Academy of Natural Sciences |

|

|

In 1868 Hadrosaurus foulkii became the first dinosaur skeleton to ever be mounted. Three stories high, the monstrous animal drew record-breaking crowds at Philadelphia's Academy of Natural Sciences.

|

|

display at the Academy of Natural Sciences, then located at Broad and Sansom Streets in Philadelphia, Pa.

Assembled on an iron latticework in a life-like pose, the three-story-high construction was the first dinosaur skeleton ever mounted anywhere in the world. It's erection by British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in concert with Academy officials Dr. Joseph Leidy and Edward Drinker Cope established the concept that would become the universal standard for all future dinosaur displays.

Awed public

For the first time, members of the public could walk up close to a prehistoric creature whose very existence was still a startling revelation to many.

Leidy had hoped the unique museum display would have some educational value, sparking a broader interest in Natural History topics and drawing a wider audience into the museum. It succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

Leidy's biographer wrote that after Hadrosaurus foulkii was unveiled, attendance at the Academy became almost "overwhelming." In fact, the crowds soon generated so much airborne dust that the institution's other collections of delicate fossils where threatened. Soon the Academy was forced to take action to limit the number of visitors. It decreased the number of days the museum was open to the public and began charging admission. But the crowds still kept coming -- not only from around the U.S. but from around the world as well.

Driven from building

About 30,000 people a year normally visited the Academy. But during the first year after Hadrosaurus foulkii went on display, the number more than doubled to 66,000. The following year, it went to 100,000. Finally, the masses, jostling to see a real dinosaur, literally drove the Academy out of its building.

As an emergency measure, the institution launched a fund-raising drive for the construction of a new facility, twice the size, at the 19th and Race Streets location it still occupies today.

For 15 years -- from 1868 to 1883 -- Hadrosaurus foulkii was the only mounted dinosaur skeleton on display anywhere in the world. In 1879, it became the first dinosaur skeleton to be displayed in Europe when the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh acquired a copy.

Thugs smash Hadrosaurus

In one of its most colorful episodes, one of five towering Hadrosaurus foulkii mounts created by Hawkins was destroyed by a gang of thugs in New York City in 1871. There, the Haddonfield fossil was scheduled to go on display at a special Central Park exhibit of prehistoric life. But for reasons that have never been made clear, Hadrosaurus foulkii drew the ire of New York's notorious political boss and municipal corruption czar William Tweed. Tweed had Hawkins' Central Park workshop ransacked and the Hadrosaurus mount not only smashed, but its parts heaved into a nearby lake as well.

In 1876, the Haddonfield dinosaur skeleton was a featured exhibit at the Centennial Exhibition of scientific and industrial wonders in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, where Edward Drinker Cope served as a consultant on prehistoric life exhibits. The fossil shared the limelight with the world's largest steam engine and the torch of the yet-to-be-completed Statue of Liberty.

Smithsonian Institution

In the late 1870s, another copy of Hadrosaurus foulkii was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution, which displayed the world-famous skeleton in its headquarters "Castle" building. In the 1880s, the specimen was moved to the Institute's Arts and Industries Building.

The popularity of the Hadrosaurus foulkii museum exhibits throughout the latter half of nineteenth century ignited a widespread public interest in dinosaurs that has never abated. The excited public response to the Haddonfield fossil also proved the commercial possibilities inherent in dinosaur discovery and display and ultimately gave rise to a flurry of museum construction and expansion across North America and Europe.

And ever since, curators have managed their galleries to highlight the menagerie of dinosaur skeletons that continue to be the most popular attractions in today's natural history museums.

|